Lean manufacturing is often taught as a battle against visible waste: overproduction, excess motion, waiting, defects, transport, inventory, and over-processing. Shops learn to map value streams, calculate takt time, and optimize flow. Yet in many CNC environments—especially high-mix, low-volume (HMLV)—the biggest lean failure is not a visible waste pile at all. It’s a time pile. Setup time quietly accumulates like hidden inventory, and because it lives inside the machine schedule, people underestimate it.

If you want a practical lean win in machining, look at your changeovers first. Setup time is where capacity disappears. It’s also where quality errors creep in and labor stress spikes. Lean is not just about cutting costs; it’s about making output predictable. Setup reduction is one of the few levers that improves cost, speed, and predictability all at once.

Setup time behaves like inventory

In lean terms, inventory is any resource sitting idle while value is not being added. We usually picture raw stock on a rack or work-in-process on a cart. But a machine sitting idle while an operator indicates and adjusts a fixture is also inventory—just time-based inventory.

Think of a typical HMLV day:

- Job A runs 25 minutes.

- Job B runs 18 minutes.

- Job C runs 40 minutes.

Each job swap needs 15–30 minutes to tear down, mount the next fixture, find zero, verify alignment, and cut a first article. Over a shift with 6–10 swaps, you might spend three hours of “non-cutting” time inside the cutting schedule. That time is inventory. It is a buffer you’re forced to carry because your setup process is not reliable enough to flow.

Lean tries to remove buffers. Setup time is a buffer disguised as a necessity.

The two lean penalties of long setups

Long setups create two kinds of waste:

- Waiting waste

The spindle is waiting for humans. Your highest-value asset is idle while tasks occur that could often be done elsewhere or made repeatable. - Batching pressure

When setups hurt, production responds by batching. “Let’s run bigger batches so we don’t have to change over.” That decision creates real inventory, slows feedback, and makes scheduling rigid. It’s the classic lean trap.

A lean CNC shop is one that changes over often and cheaply. If changeovers are expensive, your shop becomes batch-driven regardless of what your lean poster says.

Why HMLV makes setup waste explode

HMLV amplifies setup waste because:

- part variety forces frequent swaps

- fixtures are more custom

- datums vary job to job

- operators spend more time thinking than repeating

In high-volume plants, you spread setup cost across thousands of parts. In HMLV, setup costs are concentrated into tens of parts. That makes setup reduction a first-order profit driver.

The lean cure: standardize the baseline

The lean way to reduce setup time is to standardize the baseline between machine and fixture. You don’t want every fixture to reinvent its mounting strategy or datum transfer. You want a docking language: a repeatable interface that every fixture speaks.

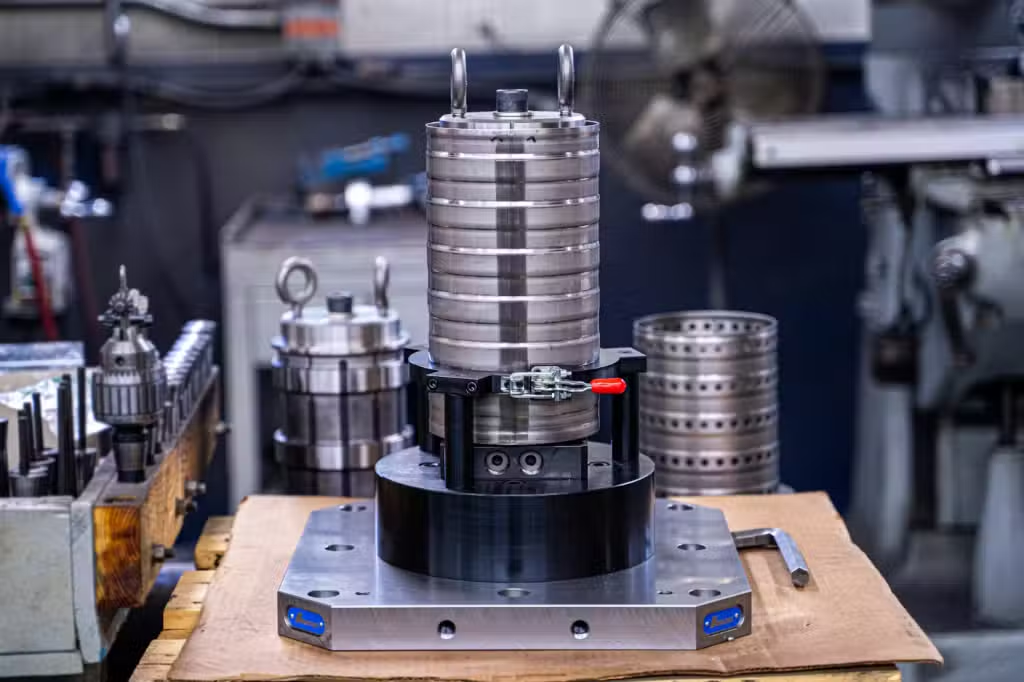

In many shops, this standard baseline is created with modular zero-point or quick-change platforms. The principle is to separate positioning (the repeatable interface) from clamping (the fixture’s job). Once positioning is standardized, changeover becomes a small, repeatable gesture rather than a custom alignment project.

A practical way to build that standardized docking layer is by adopting a repeatable modular interface such as 3r systems, allowing fixtures to be preset offline and returned to the machine without re-indicating.

Lean people will recognize this immediately: it’s SMED (Single-Minute Exchange of Dies) applied to CNC. The whole purpose of SMED is to turn internal steps (machine-stopped steps) into external steps (machine-running steps) and to make the remaining internal steps standardized.

Offline setup is SMED in action

Once the baseline is repeatable, you can push skilled tasks offline:

- clamp raw stock on a preset bench

- verify seating height

- confirm probe access

- torque down to a documented standard

- label offsets and job IDs

When the machine frees up, you simply dock the prepared fixture and start cutting. This is the single biggest lean transformation most CNC shops ever make, because it converts random setup events into predictable modules.

The “last inch” of lean setup: clamping repeatability

Lean does not end at the machine interface. If your fixture baseline is repeatable but the part is not, you still have variation. The fastest way to reduce part-level variation in general prismatic work is symmetric clamping.

Self-centering vises do two lean-friendly things:

- they remove manual centering (an internal step)

- they reduce seating and clamping variability (a defect driver)

For recurring part families, using a symmetric clamping module like CNC Self Centering Vise helps stabilize part location, cuts first-article adjustment, and supports faster, smaller batches.

How lean gains compound over time

Lean improvements compound because they free time that you can reinvest. Setup reduction yields:

- more cutting hours per shift

- less firefighting

- better quoting accuracy

- more flexible scheduling

- faster feedback to CAM and engineering

You also see cultural benefits. When operators trust the setup system, they stop hoarding machine time with batching. That changes how the whole shop behaves.

What a lean setup KPI set looks like

Don’t track ten things. Track the few that matter:

- average changeover duration

- number of changeovers per shift

- first-part pass rate (no offset tweak)

- time to restart a previously-run job

- spindle uptime percentage

If changeover time drops and changeover frequency rises while first-part pass rate holds, you are becoming lean in a real way.

Common lean anti-patterns in CNC

A few mistakes block setup-leaning:

- “We can’t standardize because every part is different.”

Your parts are different; your baseline doesn’t have to be. - “Setup is skilled work, not waste.”

Skilled work is not waste. Skilled work inside machine downtime is waste. - “We’ll fix setup by training more.”

Training helps, but repeatability is a hardware-plus-process result.

Closing thought

Lean in CNC isn’t a theory; it’s a habit of making setups cheap and repeatable enough to flow. If you standardize the baseline, shift precision tasks offline, and clamp parts symmetrically, you don’t just cut minutes—you reshape how work moves through your shop. Setup time stops acting like hidden inventory, and your machines finally behave like lean assets instead of expensive waiting rooms.